One of my explorer/adventurer hero and friend is Brett Friedman. I watch his videos every week (I have never missed one since 2020). Among his copious credentials, Brett, being a former EMT and certified in the top levels of wilderness medicine, is a Wilderness First Aid (WFA) instructor and has taught hundreds of these classes. This inspired me to take the course. The weekend of 1/10-1/12 saw me and several others from the Explorers Club Texas Chapter taking the course. On the first day of the training, I recertified my Basic Life Support (BLS) certification that had expired. I also took a mini course a few days prior to the long weekend classes, in epinephrine auto injection and got that certification. Lastly, I took the WFA training and got my certification in it.

This blog will mainly focus on the WFA training to include the agenda with hour-by-hour topics. The course was taught by two wilderness medicine experts. To give you an idea of the qualifications needed to be able to teach these courses, I want to share this with the reader. One of the instructors is a physician and she was also trained in wilderness medicine and has taught many of these classes. The other is a wilderness EMT and is currently in his first year of medical school. He has taught many WFA classes and has taught Wilderness First Responder (WFR) classes, and he also teaches other instructors trying to get qualified to teach.

In addition to the two instructors, there were 7 students taking the course. Ages ranged from a 16-year-old high school student to an 80-year-old adventurer / Explorer. Include with these two were two former Combat Veteran Marines, two first year medical students. And one other adventurer / explorer. What an awesome bonding experience. Photos from my actual course.

Small Classes Rock!

If you don’t venture into remote wilderness environments or even regular outdoor venues, why would you want to take this training? Common sense tells us that you never know when you come across someone choking, maybe the next time you eat out? You are at the mall and suddenly someone falls or worse, is having a heart attack. Do you know CPR or wound management? In our everyday lives, you may utilize something from these courses to aid someone or even save a life.

Before taking any of the wilderness medicine training, I took a mini course in epinephrine auto injection. This training comes into play assuming you come into a situation with someone experiencing anaphylactic shock. Anaphylaxis is when you have a severe allergic reaction. Most commonly, it happens after you eat certain foods or get stung by an insect. Going into anaphylactic shock can be life-threatening. If you notice symptoms of anaphylaxis, such as having trouble breathing, you will use an epinephrine injector (commonly called an Epi-pen). While I am not a doctor and could not get a prescription for an Epi-pen, the victim might have one with them as they would have a history of being susceptible to allergic reaction. If they carried a pen, I would be certified to deliver the injection.

Tom McGuire practicing self administration of an Epi-Pen injection

The prerequisite for taking WFA is having a current Basic Life Support certification. After the 2-year period, mine expired so I had to get recertified. Friday night, I relearned CPR and the use of an AED. An automated external defibrillator (AED) is a medical device designed to analyze the heart rhythm and deliver an electric shock to victims of ventricular fibrillation to restore the heart rhythm to normal.

Practicing delivering a shock to restart the heart

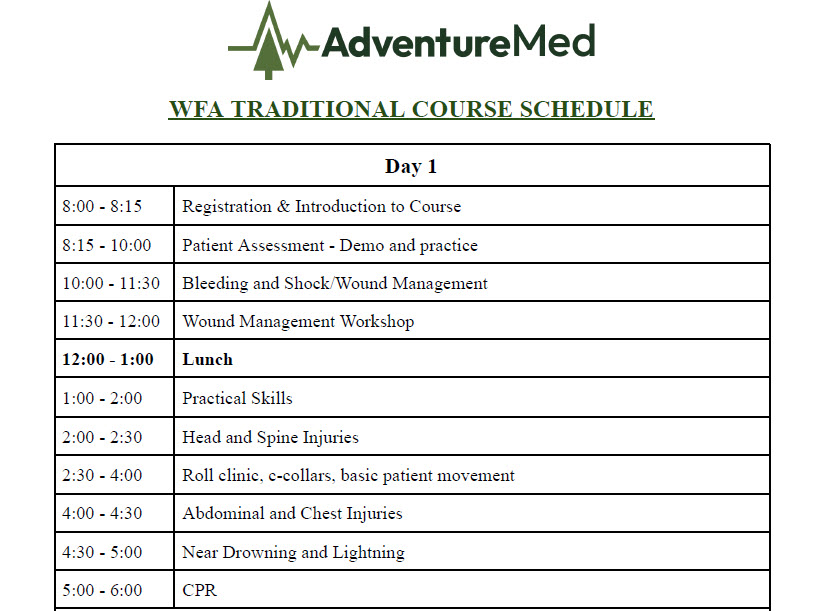

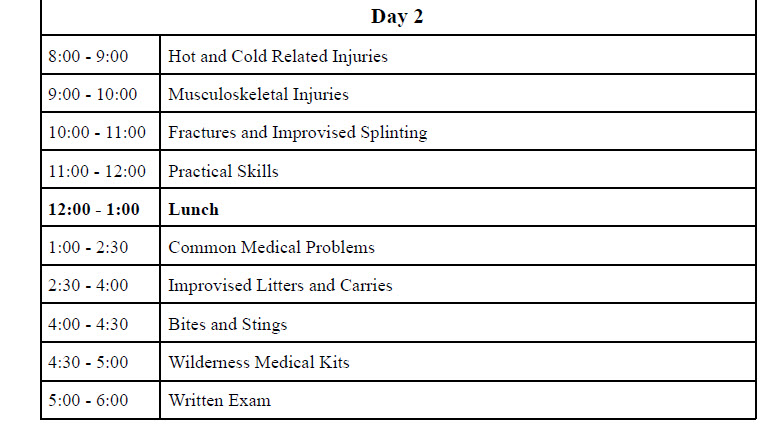

Look at the outline that follows and you will be amazed at the breath and variety of emergencies you might encounter in the wilderness or elsewhere.

You will notice at the end of the training, a test of 25 multiple choice questions is given and to pass, one must score 80% or higher.

The course combined lectures and practical scenarios where we simulated emergencies in the wilderness.

Our Instructor Heather talking about hypothermia

Simulating a head wound

Using a tarp and blankets to trap heat and raise the body temperature after the victim was pulled from an icy water river

Applying a tourniquet, tighter is better

We took this training in the field. Some of us were victims and some were responders. We took turns playing these roles. Scenarios like coming upon drownings, a mountain biker falling and having a leg fracture, a rock climber falling and having a head injury, someone getting stung and experiencing anaphylactic shock, and still someone needing us to improvise a litter to carry them in an emergency evacuation were given to us to provide first aid. There were several others, but you get the picture. At first, we stumbled in the execution of a structured assessment of the patient and the situation trying to figure out what happened, what the extent of the injuries were and how best to provide first aid. After practicing several times, we got better each time. I enjoyed these scenarios so much and the simulation of what to do as we encountered the situation.

As a former Special Forces Medic and a former Search & Rescue search manager, I had forgotten so much as I learned how to treat these emergencies many years ago. This training brought back memories for me but also brought me up to date in the current best practices for wilderness medicine.

For those wanting to work in the outdoor field or just wanting a deeper dive into wilderness medicine, there is a follow-on course. This 70-hour training certification is called Wilderness First Responder or WFR.