The Kwakwaka’wakw, also known as the Kwakiutl, are a federation of tribes, indigenous to the Pacific Northwest Coast of Canada. The Kwakwaka’wakw First Nation believe in the creation of the land, nature, and the people, and centers on the supernatural and nature’s deep connection to human existence. In their traditions, the world was shaped by powerful ancestral beings, often animals, who transformed into humans to guide and shape the land. One key figure is the Raven, a trickster and creator, who plays a central role in bringing light to the world and helping to form the Kwakwaka’wakw’s relationship with the environment and the spiritual world. Their creation beliefs emphasize respect for nature and the interconnectedness of all life. This paper is a high-level overview of their culture, history, and way of life:

The Kwakwaka’wakw once had a population estimated at around 19,000 before European contact. However, the introduction of diseases such as smallpox, along with colonial policies, dramatically reduced their numbers. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the population had dwindled to less than 2,000. In recent years, the Kwakwaka’wakw population has seen a slow resurgence, with over 5,500 registered members today, though many continue to face challenges related to cultural preservation and socioeconomic conditions.

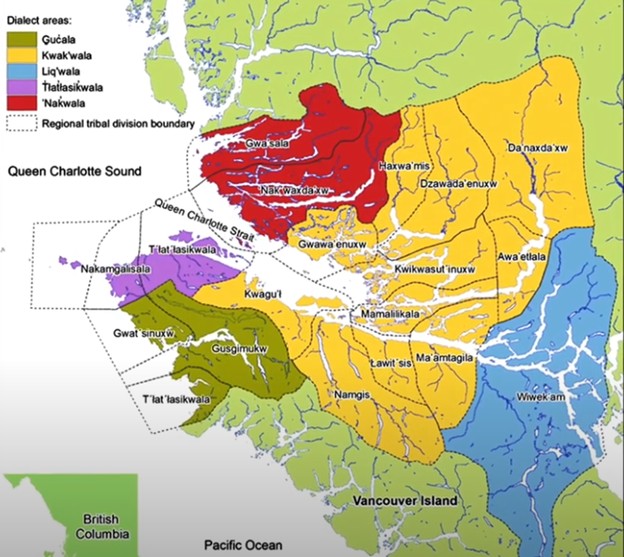

Territory: Traditionally, the Kwakwaka’wakw territory includes the northern part of Vancouver Island, the adjacent mainland to include a portion of The Great Bear Rainforest, and some smaller islands. Their land is characterized by dense forests, rugged coastlines, and abundant marine life.

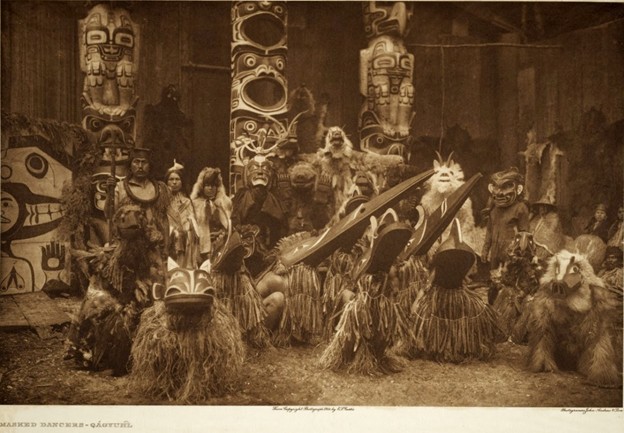

Culture and Traditions: The Kwakwaka’wakw have a rich cultural heritage that includes elaborate art, storytelling, dance, and ceremonies. Their artistic tradition is particularly renowned for its intricate wood carvings, masks, totem poles, and ceremonial regalia. Potlatches, a traditional ceremony involving feasting, gift-giving, and cultural performances, are central to Kwakwaka’wakw social and spiritual life.

Language: The Kwak’wala language belongs to the Wakashan language family and is spoken by many Kwakwaka’wakw people. Efforts are being made to revitalize and preserve the language, which is considered endangered. One such effort is led by K’odi Nelson. K’odi envisioned a center that was central to the various bands and tribes where the youth would come for a program that would bring pride through culture to young people. His vision and his methods are transforming kids by learning their native language and also their culture. He has proven that this program that he designed shows incredible improvement in the children starting within 5 days of immersion. He has built a center in Hada. Hada is the sacred center of all the tribes. Nawalakw is the foundation K’odi started and more information can be found at https://nawalakw.com/. I spoke to him about future expansion plans. It impressed me so much that I am going to try and see if I can get a grant from The Explorers Club to help his vision come to fruition. He gifted me with a Nawalakw T-Shirt. Additionally, there are many dialects spoken depending on the geographical location of the various bands as depicted by the graphic below.

Subsistence: Traditionally, the Kwakwaka’wakw relied on a combination of fishing, hunting, gathering, and horticulture for subsistence. Salmon, halibut, shellfish, and other marine resources were crucial to their diet, supplemented by hunting land mammals and gathering plants.

Social Structure: Kwakwaka’wakw society traditionally had a complex social structure with elders occupying positions of leadership and influence. Status and wealth were often determined by lineage, accomplishments, and access to resources.

Contact with Europeans: Like many Indigenous peoples in North America, the Kwakwaka’wakw experienced significant disruptions due to European contact, including the introduction of diseases, displacement from traditional territories, and cultural suppression. However, they also adapted in various ways, incorporating some European goods and practices into their culture while maintaining their distinct identity.

Contemporary Issues: In contemporary times, the Kwakwaka’wakw continue to assert their rights to land, resources, and cultural autonomy. They are actively involved in efforts to preserve their cultural heritage, revitalize their language, and promote sustainable development in their territories.

The Kwakwaka’wakw people are organized into several tribes or bands, each with its own distinct community and often its own chief or leadership structure. In total, there are 18 different tribes or bands and below are some of the major Kwakwaka’wakw tribes or bands:

- Namgis: The Namgis are one of the largest and most prominent Kwakwaka’wakw tribes. They primarily reside in Alert Bay on Cormorant Island and have a rich cultural heritage, including renowned artists and dancers.

- Kwakiutl First Nation: The Kwakiutl First Nation is based in the traditional territory of the Kwakiutl people, encompassing areas such as Fort Rupert and Port Hardy on northern Vancouver Island.

- Kwikwasut’inuxw Haxwa’mis First Nation: This First Nation consists of three Kwakwaka’wakw tribes: the ‘Namgis, Kwagu’ł, and the Haxwa’mis. They are located primarily in the northern part of Vancouver Island.

- Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Nations: This amalgamated First Nation represents the Gwa’sala and ‘Nakwaxda’xw tribes. They are located in the Port Hardy area of northern Vancouver Island.

- Tlowitsis Nation: The Tlowitsis Nation is a Kwakwaka’wakw First Nation located in the Johnstone Strait and adjacent mainland areas.

- Da’naxda’xw/Awaetlatla First Nation: This First Nation represents the Da’naxda’xw and Awaetlatla tribes, who historically inhabited areas around Knight Inlet and the surrounding region.

- Kwiakah First Nation: The Kwiakah First Nation is based in the traditional territory of the Kwiakah people, located in the southern part of the Broughton Archipelago.

- Gwawaenuk Tribe: The Gwawaenuk Tribe resides in the northern part of Vancouver Island and is part of the Kwakwaka’wakw cultural group.

These are just a few examples, and there may be additional smaller tribes, clans, or bands within the Kwakwaka’wakw nation. Each tribe or band has its own unique history, culture, and relationship with its traditional territory.

The symbol of the Kwakwaka’wakw people is deeply rooted in their rich cultural heritage and artistic traditions. One of the most iconic symbols associated with the Kwakwaka’wakw, as with many Indigenous cultures of the Pacific Northwest Coast, is the raven.

The raven holds great significance in Kwakwaka’wakw mythology and oral traditions. It is often portrayed as a trickster figure, a transformer, and a cultural hero who brings light, knowledge, and creativity to the world. The raven is associated with intelligence, wit, and adaptability, embodying important cultural values and teachings.

In addition to the raven, other common symbols found in Kwakwaka’wakw art and culture include the killer whale, bear, eagle, salmon, and various supernatural beings depicted in their traditional stories and legends. These symbols are frequently incorporated into their artwork, including carvings, masks, totem poles, and regalia, serving as a means of cultural expression, storytelling, and connection to their ancestral traditions.

The Kwakwaka’wakw people have produced many renowned artists whose works have garnered international acclaim for their craftsmanship, creativity, and cultural significance. Here are a few notable Kwakwaka’wakw artists:

- Mungo Martin (Nakap’ankam): Mungo Martin, also known by his Kwakwaka’wakw name Nakap’ankam, was a highly influential artist and cultural leader. He played a crucial role in the revitalization of Kwakwaka’wakw art and culture during the early 20th century. Martin’s totem poles, masks, and other artworks are celebrated for their masterful craftsmanship and cultural authenticity.

- Charlie James (Yakuglas/Seaweed): Charlie James, known by his Kwakwaka’wakw names Yakuglas and Seaweed, was a prolific carver and artist. He created numerous totem poles, masks, and other artworks that are prized for their intricate designs and spiritual significance.

- Willie Seaweed (Tlasutiwalis): Willie Seaweed, also known as Tlasutiwalis, was a skilled carver and artist who played a significant role in preserving and promoting Kwakwaka’wakw art and culture. His works, including masks, totem poles, and dance regalia, are celebrated for their traditional forms and innovative designs.

- Henry Hunt (Tsaqwassud): Henry Hunt, known by his Kwakwaka’wakw name Tsaqwassud, was a renowned carver and artist who helped revive Kwakwaka’wakw artistic traditions. He worked closely with Mungo Martin and other artists to create totem poles, masks, and other artworks that reflect Kwakwaka’wakw cultural heritage.

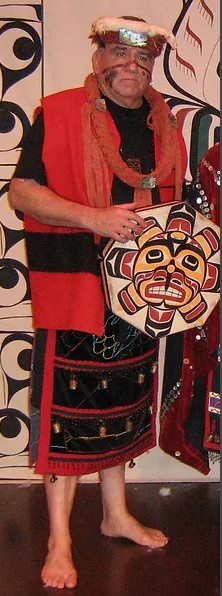

- Calvin Hunt (Kwagu’ł ) is a First Nation artist from Fort Rupert, British Columbia. He is a descendant of the renowned Tlingit ethnologist George Hunt. He was apprenticed as a teenager to his second cousin Tony Hunt, an artist and carver. He is a woodcarver and owns his own gallery. He was made a member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts.

I met Calvin in his workshop and studio. He is continuing the Kwakiutl culture through his art of carving totem poles, producing masks, drawing, and other forms to display and keep the culture alive.

- Doug Cranmer (Namugwis): Doug Cranmer, also known as Namugwis, was a highly skilled carver and artist whose works are celebrated for their innovation and contemporary style. He played a key role in the modernization of Kwakwaka’wakw art while maintaining respect for traditional forms and techniques.

Anyone interested in Kwakiutl thought and religion should check out Stanley Walens, “Feasting With Cannibals: An Essay on Kwakiutl Cosmology” (Princeton, 1981).

Important Cultural Traditions:

Two of the most prominent aspects of not only the Kwakiutl people, but other pacific northwestern nations are the significance of both totem poles and potlatch ceremonies.

Totem Poles

Totem poles are one of the most famous and significant symbols of many Indigenous tribes in North America, particularly in the Pacific Northwest region. These poles are typically made from large trees such as red cedar, intricately carved and painted with images of animals, humans, and mythical creatures. Each totem pole tells a unique story, reflecting the history, legends, and cultural values of the tribe.

Totem poles serve various functions within Indigenous communities. They may be erected to commemorate significant events such as births, marriages, or the death of a tribal member. Some totem poles are used as symbols of lineage or clan, illustrating the connections and heritage of families or tribes. Other poles may serve ceremonial purposes or mark the territory of a tribe.

The creation of a totem pole is a labor-intensive process requiring skill and dedication, typically performed by skilled artisans within the community. Carving and decorating a totem pole is not only an artistic endeavor but also a sacred act, showing reverence for ancestors and spiritual beings. Through generations, totem poles have become powerful symbols of the existence and development of Indigenous culture.

Potlach Ceremonies

A potlatch is a gift-giving feast practiced by Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of Canada and the United States.

This includes the Heiltsuk, Haida, Nuxalk, Tlingit, Makah, Tsimshian, Nuu-chah-nulth, Kwakwaka’wakw (Kwakiutl), and Coast Salish cultures. Potlatches are also a common feature of the peoples of the Interior and of the Subarctic adjoining the Northwest Coast, although mostly without the elaborate ritual and gift-giving economy of the coastal peoples.

A potlatch involves giving away or destroying wealth or valuable items in order to demonstrate a leader’s wealth and power. Potlatches are also focused on the reaffirmation of family, clan, and international connections, and the human connection with the supernatural world. Potlatch also serves as a strict resource management regime, where coastal peoples discuss, negotiate, and affirm rights to and uses of specific territories and resources. Potlatches often involve music, dancing, singing, storytelling, making speeches, and often joking and games. The honoring of the supernatural and the recitation of oral histories are a central part of many potlatches.

The Namgis of Alert Bay agreed to allow production of a video. The link to the video made by Museum of Anthropology, University of British Columbia on Potlatch filmed in Alert Bay can be found at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=InhQg1sLXSI&t=282s&ab_channel=MuseumofAnthropology.