An overview of Inuit Indigenous People of North America

Bob Rein, Ethnographer, Indigenous Cultures of North America

Member National MN’24, The Explorers Club

Allen Tuten, Ethnographer of Alaskan Indigenous Cultures

The far northern reaches of Alaska and Canada, from Tuktoyaktuk to Mittimatalik (Pond Inlet) and on to Greenland, are inhabited by Indigenous People known as Inuit. It is widely believed that they migrated from Asia across the Bering Strait land bridge. In a land so harsh with temperatures that can plummet to between −54 and −46° C (−65 and −50° F), survival means finding ways to sustain the family unit via hunting and fishing. The Inuit are masters at thriving in this frozen environment. Between imposing government regulations, climate change, and the introduction of technology and modern conveniences, the way of life for these people has changed dramatically.

Photo Credit: RAX-Ragnar Axelsson by permission

This paper is a high-level overview about these people. It examines their culture, their ability to sustain a way of life, and the issues facing them. The paper is intended to let one interested in crossing their land, gain an insight into the people of the arctic. I’m sharing it so others might use it as a starting point for their adventure.

Background:

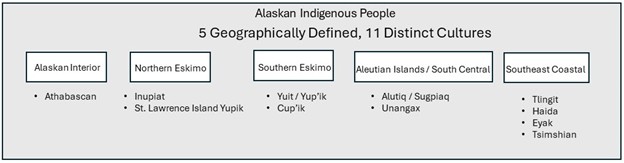

Many of us grew up thinking that these people of the far north were called Eskimos. Today we hear them referred to as Inuit. Some people associate them with Inupiat. This section is an attempt to clarify the three names. In the chart below, we can see that if we look at a breakdown of geography and linguistics of the Alaskan Indigenous people, we see how the term Eskimo is properly positioned.

The terms Inuit and Inupiat also refer to Indigenous peoples of the Arctic regions, but they are distinct groups with different cultural, historical, and geographical backgrounds. Here’s a breakdown of each:

Inuit

- Geographical Location: The Inuit primarily inhabit the Arctic regions of Canada, Greenland, and parts of Alaska.

- Cultural Identity: Inuit is an umbrella term that refers to various Indigenous groups who share similar linguistic and cultural traits. The term “Inuit” means “the people” in the Inuktitut language.

- Language: The Inuit speak various dialects of the Inuit language, which belongs to the Eskimo-Aleut language family. There are three distinct dialects:

- Inuvialuktun, spoken in Sachs Harbour (NE of Tuk), Paulatuk (Due E of Tuk), Tuktoyaktuk, Aklavik (SW of Tuk), and Inuvik (S of Tuk). Tuk is short for Tuktoyaktuk, a community on the northern tip of the Northwest Territories on the Arctic Ocean.

- Inuinnaqtun, spoken mostly in Ulukhaktok (NW of Cambridge Bay)

- Inuktitut, whose speakers often live in Yellowknife and regional centers.

- Historical Context: The Inuit traditionally relied on hunting, fishing, and gathering, with a focus on sea mammals like seals, whales, and walrus. They are known for their innovations in tools, clothing, and transportation (e.g., the kayak and the igloo).

- Countries: Canada (particularly the Inuit regions of the North), Greenland, and Alaska (U.S.). In Canada, Inuit are recognized as a distinct group alongside First Nations and Métis people.

Inupiat

- Geographical Location: The Inupiat primarily live in Alaska, especially in the northern and northwestern parts of the state.

- Cultural Identity: The Inupiat are a subgroup of the broader Inuit cultural family. They share many similarities with the Inuit, including language and subsistence practices, but have their own distinct cultural and historical identity, particularly shaped by the specific environments and histories of Alaska.

- Language: The Inupiat speak Inupiatun, which is a dialect of the Inuit language. It is part of the larger Eskimo-Aleut language family, but it is distinct from other Inuit dialects.

- Historical Context: Like other Arctic peoples, the Inupiat traditionally depended on hunting and fishing, with a strong emphasis on marine life. They are known for their deep connection to the land, sea, and wildlife, which sustains their communities.

- Countries: The Inupiat live primarily in Alaska, where they are part of the broader Alaska Native population.

Key Differences:

- Geography: The Inuit are spread across Canada, Greenland, and parts of Alaska, while the Inupiat are specifically from Alaska.

- Cultural Nuances: While both groups share similar practices and linguistic roots, the Inupiat have distinct cultural traits and histories tied to Alaska’s unique environment.

In summary, all Inupiat are Inuit, but not all Inuit are Inupiat. The Inupiat represent a specific cultural and linguistic group within the broader Inuit family.

~~~~~~~~

The Indigenous peoples of the north face challenges that deeply affect their way of life. Among those challenges are government regulations, especially around hunting and fishing, social issues, and climate change.

History has not been kind to the Indigenous people. While conditions have improved and are continuing to improve, Indigenous people have some deep hurdles to overcome.

There is a basic distrust of outsiders, those attempting to help and those trying to exploit. This is based on how various forces inflicted unwanted cultural changes.

To illustrate and reflect on the issues facing the people and the observations Allen Tuten (bio at the end) came away with on his multiple interactions with the Inuit, we give the reader a glimpse into their lives:

“From stories I have been told by some of the elders, I have learned of gross atrocities inflicted upon the culture and existence of the indigenous people. In the Aleutian Island chain early Russian fur traders forced the people to hunt and provide animal skins for them for many years. Stories are even told of the people being shot to death for sport by the intruders. When I was in Dutch Harbor in the 1990’s with a volunteer group doing painting and minor repairs, we were told these stories. The native descendants of these people are still skeptical of outsiders. While painting the house of an elderly lady, she did not come outside to greet us. But later in the day we saw her peeking out from the corner of a curtain window. The second day we saw her full face in the window. On the third day, this eighty-year-old lady came out of her house with a plate of fresh cookies. That change made the whole trip worthwhile.”

He further relates: “Another summer working in the lower panhandle of Alaska, we were told of other hardships forced on the people by the Russian fur traders.”

Our own society has also been guilty of forced cultural change. Missionaries, in the 1800’s made their way into Alaska denouncing their thoughts on faith in the name of Christianity. They also set up schools for the children where English only was allowed and their native language, culture and skills not permitted.

There are many ramifications to the people from the forced moves from ancestral villages to urban and other locations. Allen learned of the injustices firsthand. “In order to “reeducate” the children, many were taken from remote villages and brought into the missionary schools. I spent many summers in Nome, Alaska and gathered stories from elders there. One told me of her family being forced to move from their island village of Little Diomede to the mainland. Little Diomede is a very remote island near the border with Russia. It is mostly a rocky island with sheer cliffs all around. This small village had occupied this rock of land for centuries. Life was hard, but it was their life and culture. Every resident was forced off the island to the mainland, where they could be “better taken care of”. This lady in tears told me before they had a home and family unit that worked together to survive. On the mainland, their skill set for survival was not the same. She said now her family unit was broken and destroyed by alcoholism.

Little Diomede is no longer inhabited. I have been to St Lawrence Island visiting the villages of Gambel and Savoonga. Gamble is about ninety-five percent native Alaskans. Housing and communities exist with no street patterns, just random housing, a church and school. There was one convenience store with limited inventory. What I remember most about Gambel was a massive area with layers upon layers of walrus, whale and seal bones. This must have been the dump site for hundreds of years.

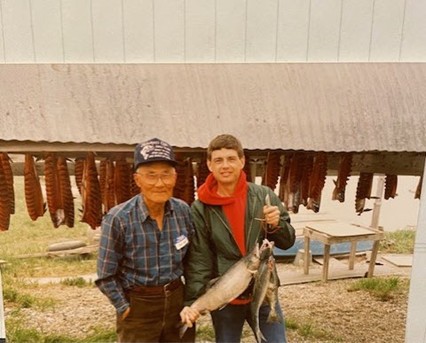

Photo courtesy of Allen Tuten taken on his visit to Gamble, AK

Curiously, I wandered around this area looking and saw discarded tools or artifacts until I was approached by one of the locals and was told only the native Alaskans could wander there. I apologized and left. He later brought me a slate ulu (knife) several hundred years old and offered it for sale.”

All the above have led to social issues the Inuit face. Alcoholism is an issue and has forced communities to combat this, sometimes enacting bands on the sale of alcohol. Allen offers these observations. “During my time in Nome, I witnessed firsthand the issues with alcoholism. Generations later and after some of the forced changes, many have not adapted to an urban lifestyle. With boredom and long dark winters, some turn to alcohol. It is such a problem that some villages have banned the sale of alcohol. (I have observed this same issue while working in The Navajo Nation in Northern Arizona)”

Housing and education inequities exist for these people. Both are substantially inadequate and below what non-native people enjoy. “Housing is substandard in some of the remote villages compared to our concept of what a house should be like. However, I have visited some of the small, wood frame, unpainted houses in the remote villages. A family of six may be living in just two or three rooms. Visiting in one of the homes in Teller, Alaska, there was very little furniture, limited electricity and appliances. The dad was sitting on the floor of the living room/kitchen cleaning fish. Outside a seal skin was stretched on a frame drying and seal meat was cut into strips drying in the sun. This would be food for later. They didn’t have much by our standards, but the family was together and seemed happy.”

Hunting and fishing, vital to sustaining life, are impacted by government regulations and climate change. “Much of traditional hunting and fishing has been diminished due to environmental change and over harvesting. Government regulations have also limited open harvesting, but native Alaskans are given special rights for substance hunting and fishing in most areas. I am most familiar with this on the North slope and Northwest Alaska where there is still a large part of the population of native heritage. This area is very remote and getting food & supplies by small air service is extremely expensive making bounty of the land and sea critical.”

Allen sums up his feelings of Alaska and its native people from his 26 forays over 34 years.

“I have been pleased to see in recent years the encouragement of young people to learn their ancestral language, crafts and customs. They proudly show these relearned craft skills, cultural dances, and language at festivals and special events.

A young Allen Tuten and an Eskimo elder, Sam Kakic

Twice at the Whaling Festival in Utqiagvik (Barrow) I have participated in some of these activities such as, helping to cut up a whale for distribution to all families, the walrus skin blanket toss (The walrus skin toss is an old hunting maneuver to throw a spotter high into the air to look for game on the frozen sea), and other games.

Picture courtesy of Allen Tuten at Utqiagvik (Barrow, AK)

Even the reversion of the names of some villages back to its original name is progress in restoring the culture of the indigenous people. I hope that the sacred mountain Delali will not be changed again to Mt. McKinley.

In the small, scattered, remote villages in the far north of Alaska where inhabitants make up most of the population, the culture of the Inuit seems to be embraced and is a part of their daily lives. Some traditional ways I observed seem to work for the modern-day Inuit. While there are very few or no automobiles and trucks, there is an abundance of four wheelers and snow machines. They have replaced the dog sled for the most part.

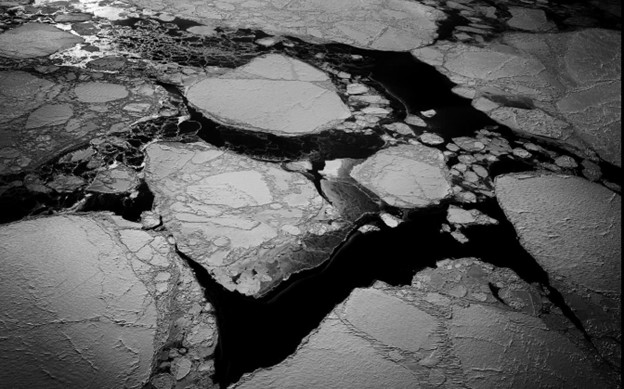

A skin boat on a Beaufort Sea partially frozen over. Photo courtesy of Allen Tuten

The people, culture and natural beauty of Alaska is amazing. I have been blessed to experience some of this firsthand. It has been especially gratifying to share their food, their lives and visits in their homes and being able to work alongside them. If the only way you can go to Alaska is on a cruise, do it, but know you will only get the tourist version.”

~~~~~~~

Photo Credit: Joe Sheppard. An Inuit family in front of a tupiq (a tent made of animal skins and used in the warmer months) at Pond Inlet in 1906

Government Regulations:

Impact of Government Regulations on Indigenous People of the Arctic: Hunting and Fishing

Indigenous peoples of the Arctic, including those in Alaska, Canada, and Greenland, have lived for millennia through hunting and fishing practices that are deeply intertwined with their cultural, social, and economic traditions. These practices are essential not only for sustenance but for maintaining connections to the land and the natural world. However, government regulations in these regions, designed to manage resources and protect the environment, have increasingly impacted Indigenous communities, particularly regarding hunting and fishing. These regulatory bodies have implemented a variety of regulations governing hunting and fishing activities. These regulations are aimed at sustainable management of wildlife, conservation of ecosystems, and sometimes economic development. However, the impact on Indigenous communities varies by region and can be both beneficial and detrimental. This section examines how these regulations are affecting Indigenous people, exploring both challenges and efforts to reconcile traditional practices with modern governance.

Alaska

In Alaska, hunting and fishing regulations are largely governed by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game and federal agencies like the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Indigenous Alaskan groups, such as the Inupiat, Yupik, and Aleut, rely on hunting marine mammals like seals, walruses, and whales, as well as freshwater fish, such as salmon, for sustenance. However, increasing regulatory measures have restricted access to certain species, particularly during breeding seasons or due to concerns about over-harvesting.

Restrictions on the hunting of bowhead whales have been implemented due to concerns over populations, while fishing quotas have limited the number of salmon that can be harvested. Additionally, modern regulatory mechanisms that require permits for hunting and fishing have placed significant burdens on traditional practices. Indigenous communities have voiced concerns that these regulations do not always consider their deep knowledge of the land and ecosystems, or their reliance on subsistence hunting.

Canada

In Canada, the federal government enforces a range of regulations governing hunting and fishing, with additional provincial rules. Indigenous groups in the Arctic, such as the Inuit, Cree, and Dene, have a long history of hunting caribou, seals, whales, and fishing in the North. Under the Canadian constitution, Indigenous rights to hunt and fish are protected, but this has not prevented regulatory changes that sometimes conflict with traditional practices.

One example is the regulation of seal hunting, which has been contentious. While Inuit communities have argued that they have a constitutional right to hunt seals for food and cultural purposes, international pressure and animal rights campaigns have led to restrictions on the sale of seal products, impacting these communities’ economies. Additionally, quotas and licensing systems for fishing in the North have complicated access to fish stocks, such as salmon and Arctic char, affecting both food security and cultural practices.

In many areas, efforts to reconcile conservation concerns with Indigenous rights have led to co-management agreements, allowing Indigenous communities to have a say in how local wildlife populations are managed. However, these agreements have been slow in some regions, and regulatory frameworks can still be difficult to navigate for Indigenous hunters and fishers.

Greenland

Greenland, an autonomous territory of Denmark, is home to a predominantly Inuit population whose livelihoods and cultural practices are similarly based on hunting and fishing. Regulations here are often shaped by both national laws and the interests of Denmark, alongside Greenlandic self-government. Key species hunted include seals, whales, and reindeer, while fish like Greenland halibut and Arctic char are also crucial to the diet.

Government regulations have targeted over-hunting and over-fishing, particularly in the context of global environmental concerns such as climate change and declining populations of certain species. For instance, quotas have been introduced for whale hunting, particularly in the face of international opposition to whaling. While Greenlandic communities argue that their hunting practices are sustainable and necessary for cultural survival, international regulations and pressures from non-governmental organizations have limited their ability to manage these resources on their own terms.

The Challenges Faced by Indigenous Communities

The introduction and enforcement of government regulations have created several challenges for Indigenous people in the Arctic:

Loss of Autonomy Over Resource Management

Indigenous communities in Alaska, Canada, and Greenland traditionally managed natural resources through their own systems, grounded in centuries of ecological knowledge. However, modern regulations often ignore this traditional knowledge and impose bureaucratic systems that undermine Indigenous governance. This loss of autonomy has been a source of tension, particularly in cases where communities feel they are being excluded from decision-making processes about their lands and resources.

Economic and Cultural Impact

Hunting and fishing are not just economic activities but are integral to the cultural identity of Indigenous peoples. Restrictions and quotas on species often limit the availability of essential food sources, leading to higher costs for store-bought food in remote Arctic communities. This can result in food insecurity, as many Indigenous people rely on hunting and fishing to meet their nutritional needs. Additionally, the reduction of hunting and fishing opportunities can erode cultural practices, as younger generations may not have access to the traditional knowledge associated with these activities.

Environmental and Climate Change Pressures

Climate change has compounded the challenges faced by Indigenous communities in the Arctic, where warming temperatures are altering migration patterns of animals and changing the availability of fish. Government regulations, which are often based on outdated models of ecosystem health, may fail to adjust quickly enough to these environmental shifts. As a result, Indigenous communities may be further disadvantaged by regulations that do not account for the rapid changes in their environment.

Efforts Toward Reconciliation and Collaboration

While government regulations have posed challenges, there have been efforts to address these issues through collaborative governance structures and legal mechanisms.

- Co-management Agreements

In many regions, such as Canada and Alaska, co-management agreements have been established to allow Indigenous groups to work with governments to manage natural resources. These agreements are intended to balance conservation efforts with Indigenous rights, allowing local communities to participate in decision-making processes. For example, the Inuvialuit in Canada have established co-management agreements that give them a role in managing wildlife populations, ensuring that their traditional knowledge is incorporated into the process.

- Legal Protections

In Canada, the constitutional recognition of Indigenous hunting and fishing rights has provided a legal foundation for challenging regulations that limit these activities. The landmark Supreme Court decision in R. v. Sparrow (1990) affirmed the right of Indigenous people to fish for food, while also allowing governments to impose restrictions if they are justified under certain conditions, such as conservation. These protections have provided a framework for ongoing negotiations between Indigenous groups and the government regarding hunting and fishing rights.

- International Advocacy

On the international stage, Indigenous groups in the Arctic have become vocal advocates for their rights to hunt and fish. They have worked with international organizations, such as the United Nations, to raise awareness about the importance of traditional subsistence practices. This advocacy has sometimes led to modifications in international treaties and regulations, allowing more flexibility for Indigenous communities to continue their practices in a sustainable manner.

Some Final Thoughts on Government Impact:

Government regulations on hunting and fishing in the Arctic have significantly impacted Indigenous peoples in Alaska, Canada, and Greenland. While these regulations are designed to conserve resources and manage wildlife populations, they often fail to account for the specific needs and traditional knowledge of Indigenous communities. The challenges include a loss of autonomy, economic hardship, and cultural erosion. However, efforts such as co-management agreements, legal protections, and international advocacy have provided avenues for reconciliation and collaboration, offering hope for a more balanced approach that respects both conservation goals and Indigenous rights. Ultimately, future regulatory frameworks will need to more effectively incorporate Indigenous knowledge and governance systems to ensure the sustainability of both the environment and Indigenous cultures.

Social Issues:

Social Issues Affecting Indigenous People of the Arctic (Alaska, Canada, Greenland)

Indigenous peoples of the Arctic, including those from Alaska (USA), Canada, and Greenland, have lived in the northernmost regions of the world for thousands of years. However, the modern challenges they face are numerous, rooted in historical injustices, environmental changes, and socio-economic struggles. This section seeks to address the key social issues affecting these Indigenous peoples, highlighting challenges related to culture, health, education, housing, environmental change, and political representation.

- Cultural Erosion and Language Loss

One of the most profound issues faced by Indigenous Arctic communities is the erosion of their culture and languages. Colonization by European powers, including Denmark in Greenland, the United States in Alaska, and the British in Canada, led to forced assimilation policies, which aimed to undermine Indigenous cultures and languages. These efforts often included the establishment of residential schools where children were removed from their communities and forbidden to speak their native languages or practice their traditions.

Despite significant cultural resilience, many Indigenous languages in the Arctic are endangered. The Inuit and other Arctic Indigenous languages, such as Inuktitut and Kalaallisut, face the risk of extinction due to the dominance of English, French, and Danish in education, media, and government. Language is crucial for the preservation of traditional knowledge, including subsistence hunting practices, storytelling, and spiritual beliefs, and its loss can lead to a disconnection from identity and heritage.

Efforts to revitalize these languages and cultures are ongoing, with programs focused on language immersion, community workshops, and the use of modern technology to preserve oral traditions.

- Health Disparities

Health disparities between Indigenous Arctic peoples and non-Indigenous populations are significant. In the Arctic regions of Alaska, Canada, and Greenland, Indigenous peoples experience a range of health issues, many of which are exacerbated by social determinants of health, such as poverty, lack of access to quality healthcare, and inadequate housing.

Key health concerns include:

- Mental Health and Suicide: Suicide rates among Indigenous youth in Arctic regions are disproportionately high. The isolation of many communities, coupled with the impact of historical trauma, cultural dislocation, and substance abuse, contributes to these high suicide rates. Additionally, mental health services are often insufficient or inaccessible in remote areas.

- Chronic Diseases: Indigenous Arctic communities face higher rates of chronic diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and obesity. These are often linked to dietary changes, with traditional foods being replaced by imported, processed foods that are less nutritious.

- Infectious Diseases: Infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis and respiratory infections, remain a concern, particularly in remote areas with limited access to healthcare services.

Efforts to address these health disparities include community-based health programs, increasing the number of healthcare professionals in remote areas, and traditional healing practices that integrate Indigenous knowledge with modern medicine.

- Education and Employment

Education levels among Indigenous Arctic populations are often lower than those of non-Indigenous populations, with many communities lacking adequate schooling resources. Schools in remote Arctic regions may be understaffed, poorly funded, and ill-equipped to provide quality education. Additionally, culturally relevant education that includes Indigenous knowledge and languages is frequently absent.

The gap in education also contributes to the lack of employment opportunities. Many Indigenous people in the Arctic struggle to find jobs that match their skills, and a lack of higher education options leads to lower levels of employment in skilled industries. High unemployment rates are prevalent in many Indigenous communities, particularly in Greenland, Alaska, and Canada.

Efforts to improve education in these regions include increasing funding for remote schools, providing scholarships, and establishing educational programs that are culturally sensitive and incorporate Indigenous ways of knowing and being.

- Housing and Infrastructure Challenges

Housing is a major social issue in many Indigenous communities in the Arctic. Due to the harsh Arctic climate and isolation, many homes are inadequate, overcrowded, and in need of significant repair. Housing shortages and poor infrastructure are widespread, particularly in small, remote villages. In Alaska and northern Canada, homes are often subject to permafrost and freezing conditions, which leads to building instability. Many communities also lack basic services such as sanitation, clean water, and electricity.

Additionally, the cost of living is high in the Arctic regions, with food and fuel prices soaring due to logistical challenges, and many families struggle to afford necessities.

Governments and Indigenous organizations are working to address these issues through funding for new housing projects, infrastructure improvements, and sustainable development initiatives. However, progress has been slow, and much more needs to be done.

- Environmental Change and Impact on Traditional Lifestyles

Climate change poses a significant threat to the traditional lifestyles of Indigenous Arctic peoples. These challenges and how they are being addressed are detailed in the next section.

- Political Representation and Self-Determination

Political representation and self-determination remain critical issues for Indigenous peoples in the Arctic. Despite significant progress in recognizing Indigenous rights, many communities still face challenges in asserting political autonomy and managing their own affairs. The legacy of colonialism and the imposition of national borders has often resulted in the marginalization of Indigenous voices in governance and decision-making processes.

In Alaska, Canada, and Greenland, Indigenous groups have fought for greater political representation and self-governance, with varying degrees of success. In Canada, the recognition of Indigenous rights and the signing of land claims agreements have empowered some communities, but others remain in legal battles over land rights and sovereignty. Greenland, an autonomous territory of Denmark, has seen increasing calls for full independence, led by the Inuit population.

There have also been significant advances in political activism and Indigenous-led movements, with leaders advocating for land rights, cultural preservation, and greater autonomy in governing their territories.

Some Final Thoughts on Social Issues:

Indigenous peoples of the Arctic face a wide array of social issues that stem from centuries of colonization, environmental changes, and socio-economic challenges. While there has been some progress in addressing these issues, much remains to be done. The resilience of Arctic Indigenous peoples, their connection to the land and sea, and their efforts to preserve their cultures, languages, and traditional ways of life are central to their ongoing struggle for justice and equity.

To address these issues effectively, it is essential for governments, Indigenous organizations, and international bodies to work collaboratively with Indigenous communities, ensuring that their voices are heard, their rights are respected, and their cultures are supported. Only through such cooperation can a more equitable and sustainable future be achieved for the Indigenous peoples of the Arctic.

Climate Change:

In the Arctic regions of Alaska, Northern Canada, and Greenland, climate change is progressing at a faster rate than elsewhere on Earth, with temperatures rising at more than twice the global average. Indigenous peoples in these regions are directly experiencing the impacts of a rapidly changing environment, from melting sea ice and shifting wildlife migration patterns to unpredictable weather events.

Thermokarst is a type of terrain characterized by very irregular surfaces of marshy hollows and small hummocks formed when ice-rich permafrost thaws. The land surface type occurs in Arctic areas. (Wikipedia definition). Jon Waterman, in his book “Into the Thaw”, references how a large landslide effected an Inupiat village. A large landslide thermokarst dumped metric tons of sediment into the Selawik River thereby impacting subsistence fishing for the Inupiat village. He offered this to share his feelings. “It’s not a benign landscape and the consequences not only to the vegetation, but to wildlife and to the people.” Another take on the implications of the landslide is the altering of the vegetation that Caribou eat, causing them to move to other feeding areas. Caribou are an important source of meat for the Indigenous people all over the arctic.

Also in his book, Waterman relays that the Inupiat had come to realize the future and how climate changes would have an impact on their lives. I’m including an excerpt from Waterman’s book. “An Inupiat prophet, Maniilaq. foretold of changes that would take place. He said that people would come from the south and east with white-colored skin. Before he disappeared somewhere in the east, he warned the people. His prophecies cited people coming on ships and through the air. He spoke of these people pulling things from the ground that would make them rich. He predicted a famine for the Inupiat.”

As traditional stewards of the land, Indigenous people possess valuable knowledge and insights into their local environments. They are key players in advocating for and driving the necessary changes to combat climate change. By working collaboratively with climate change experts, Indigenous communities are not only preserving their cultural heritage but also contributing to global climate action through their unique knowledge and solutions.

Photo Credit: RAX-Ragnar Axelsson by permission

In this section, it is important to understand what is being done to combat the effects of climate change. First, we will look at how the people of the region are collaborating with experts. Then, as a member of The Explorers Club, the international organization that has been supporting scientific expeditions and research of all disciplines, the following shows how the club is supporting Indigenous communities of the north.

How Arctic Indigenous Peoples Are Collaborating with Climate Change Experts to Bring About Change

Indigenous knowledge, often referred to as Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), is a body of knowledge developed over generations that integrates a deep understanding of the local environment, ecosystems, and climate. For Indigenous communities in the Arctic, TEK is inherently tied to their survival, cultural practices, and identity. This knowledge includes information on animal migration patterns, weather systems, plant growth cycles, and sustainable resource management techniques that have enabled these communities to thrive in the harsh Arctic environment.

In many instances, Indigenous peoples have observed changes in their environment long before scientific data confirmed these shifts. Their firsthand experience with melting sea ice, unpredictable weather patterns, and changes in animal behaviors gives them valuable insight into how climate change is manifesting in the Arctic region.

Collaboration with Climate Change Experts

Recognizing the importance of both scientific knowledge and Indigenous wisdom, there has been an increasing push for collaboration between Arctic Indigenous communities and climate change experts, including scientists, environmental organizations, and policy-makers. These collaborations take several forms, ranging from community-based research to advocacy efforts aimed at shaping national and international climate policies.

- Community-Based Monitoring and Research

Indigenous communities have been instrumental in gathering data on climate impacts, which is often integrated into scientific research. For example, Inuit communities in Canada and Alaska have been involved in monitoring ice thickness, animal populations, and changes in vegetation. Their local knowledge is used alongside satellite data and scientific observations to create a more complete and more accurate picture of climate change in the Arctic. These joint efforts are vital in understanding the nuances of climate change at a local level, which is often overlooked in broad-scale scientific studies.

A prominent example of such collaboration is the Inuit Knowledge Project, which involves sharing traditional knowledge alongside scientific data to monitor the impacts of climate change on the environment and human health. This initiative has resulted in more localized, community-driven climate action plans, where Indigenous knowledge helps tailor solutions to the specific needs of different Arctic regions.

- Advocacy for Indigenous Rights and Climate Justice

Indigenous groups are not only working with scientists to adapt to climate change, but they are also advocating for climate justice. They emphasize that climate change disproportionately affects their communities, and they are calling for policies that respect their rights, land, and sovereignty. Many Indigenous leaders argue that they should be included in decision-making processes related to environmental protection, conservation, and climate mitigation strategies, as they have the traditional knowledge to contribute valuable insights.

For instance, the Arctic Council, an intergovernmental forum consisting of eight Arctic states, includes Indigenous representatives, such as the Inuit Circumpolar Council, who help ensure that Indigenous voices are heard in high-level discussions about the Arctic environment. In addition, Indigenous peoples are pushing for the recognition of their rights in global climate agreements, such as the Paris Agreement, demanding that their ancestral knowledge and rights to land and resources be incorporated into national and international climate policies.

- Adapting Traditional Practices to New Realities

Some Indigenous communities are adapting traditional practices to respond to changing environmental conditions. For example, in Alaska, the Iñupiat people are using modern technology to track caribou migration, combining GPS tracking systems with traditional hunting methods. In Greenland, the Kalaallit people are adapting their sea ice navigation skills to the rapidly changing ice conditions, using GPS devices to supplement their traditional knowledge and ensure safe travel.

By blending traditional ecological practices with modern science and technology, Arctic Indigenous peoples are creating new methods of resource management and adaptation that not only preserve their cultural heritage but also provide models for broader climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies.

Impact of Collaboration

The collaboration between Indigenous peoples and climate change experts is already showing significant results in terms of policy influence, community resilience, and climate science.

- Strengthening Climate Adaptation Efforts

Indigenous-led adaptation initiatives are leading to more resilient communities. For example, in the Russian Arctic, Indigenous communities are building new housing that considers the changing permafrost conditions, which are thawing and causing buildings to collapse. Similarly, in Canada, the Yukon First Nations are working to safeguard their food security by mapping out changes in caribou migration and developing sustainable hunting strategies that account for those changes.

- Influence on Global Climate Policy

The active participation of Indigenous peoples in international forums, such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Arctic Council, has contributed to the integration of human rights and Indigenous knowledge into global climate policies. Indigenous advocacy has also been influential in pushing for increased climate finance for adaptation in the Arctic and other vulnerable regions.

- Raising Awareness of the Arctic’s Climate Crisis

By joining forces with climate change experts, Indigenous communities have been able to raise awareness about the severe climate impacts facing the Arctic. Through shared research, joint advocacy, and public campaigns, they have brought global attention to the disproportionate effects of climate change on the Arctic and Indigenous ways of life. This has led to greater political will to support policies that reduce carbon emissions and protect Indigenous rights.

~~~~~~~~~

How Members of the Explorers Club Are Working with Indigenous Peoples in Alaska, Northern Canada, and Greenland to Combat Climate Change

Members of the Explorers Club, which promotes scientific exploration, have been collaborating with Indigenous communities in Alaska, Northern Canada, and Greenland to combat climate change. These partnerships are vital in combining traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) with scientific research to develop adaptive and mitigation strategies tailored to the unique challenges of the Arctic.

The Role of Indigenous Knowledge in Combatting Climate Change

Indigenous communities in the Arctic have developed a deep connection with the land, sea, and wildlife over millennia. Their traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) offers invaluable insights into how ecosystems function and how they are being impacted by climate change. Indigenous peoples in these regions observe environmental shifts in ways that scientific data alone may not capture, such as changes in ice thickness, weather patterns, and animal behaviors.

TEK is crucial in guiding climate adaptation efforts and providing context for scientific research. Many members of the Explorers Club working in these regions are seeking to bridge the gap between modern climate science and Indigenous knowledge, ensuring that both are integrated into strategies to mitigate and adapt to climate change impacts.

Collaborative Projects Between Explorers Club Members and Indigenous Peoples

- Alaska: Arctic Research and Ice Monitoring

In Alaska, the Iñupiat and other Indigenous groups have long relied on sea ice for transportation, hunting, and fishing. However, the rapidly diminishing sea ice poses a serious threat to their way of life. Explorers Club members, including environmental scientists and Arctic researchers, have partnered with Indigenous communities to monitor sea ice conditions and gather data on how these changes are affecting local ecosystems.

One example of this collaboration is the Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S. (ARCUS), which works closely with Indigenous organizations like the Alaska Native Science Commission to gather traditional knowledge about ice conditions, wildlife populations, and weather patterns. This data is integrated with modern climate models to improve forecasting and support community-driven adaptation strategies. Additionally, Explorers Club members have helped develop early-warning systems to assist hunters in identifying safe ice routes, thereby reducing the risks posed by thawing ice.

Through these collaborations, Alaska Native communities are not only adapting their practices to new environmental realities but also ensuring their voices are heard in national and international policy discussions about Arctic climate change.

- Northern Canada: Monitoring Wildlife and Protecting Traditional Knowledge

In Canada’s northern provinces, Indigenous groups such as the Inuit, Cree, and Dene are facing significant changes to wildlife populations, including the migration of caribou, fish, and other animals crucial to their subsistence lifestyles. In response to these challenges, Explorers Club members have teamed up with Indigenous communities to monitor animal populations, track environmental changes, and document traditional knowledge related to hunting practices.

One notable project is the Inuit Knowledge Project, which brings together scientists and Inuit community members to study the effects of climate change on wildlife and food security. The project combines satellite tracking of caribou with Inuit observations of herd movement, creating a more complete picture of how climate change is affecting migratory patterns. By working together, Indigenous knowledge and scientific data are used to inform policies that aim to protect wildlife habitats and ensure food security for these communities.

Additionally, Indigenous communities in Northern Canada are involved in climate adaptation planning, focusing on preserving traditional practices such as hunting, fishing, and gathering. Through these collaborations, Explorers Club members help amplify the role of Indigenous peoples in developing sustainable climate solutions that protect both the environment and local cultures.

- Greenland: Addressing Ice Sheet Melting and Sea Level Rise

Greenland, home to the Kalaallit Inuit, is witnessing the accelerated melting of its ice sheet, contributing to rising sea levels that threaten coastal communities. In Greenland, the melting ice also disrupts traditional practices such as hunting and fishing, as well as infrastructure that depends on stable permafrost. Members of the Explorers Club, including glaciologists and climate scientists, are working closely with Indigenous Greenlandic communities to monitor changes in ice conditions and mitigate the effects of sea-level rise.

One of the key collaborations is the Kalaallit Climate Adaptation Program, where Indigenous leaders and climate experts are working together to assess the impact of ice sheet melting on the environment and communities. By integrating traditional knowledge about local ecosystems and ice conditions, these partnerships are helping develop more accurate climate models that predict future sea-level rise and extreme weather events.

Explorers Club members are also supporting efforts to protect Greenland’s coastal infrastructure by combining modern engineering solutions with local knowledge of how the landscape responds to seasonal changes. In some cases, traditional methods such as using local materials to stabilize coastal areas are being adapted to modern environmental management practices, ensuring both environmental protection and cultural preservation.

Impact of These Collaborations

- Strengthening Climate Adaptation Strategies

Through these collaborations, Indigenous communities in Alaska, Northern Canada, and Greenland are developing more resilient systems to cope with the impacts of climate change. For example, in Alaska, the integration of TEK with scientific data has led to improved ice safety protocols and hunting practices that account for changing ice conditions. Similarly, in Greenland, the combination of traditional knowledge and climate science has led to better coastal management strategies that protect both the environment and local populations.

These projects are not only about adaptation but also about ensuring that Indigenous knowledge systems are respected and incorporated into broader climate policy and action. By integrating TEK into scientific research and climate models, these partnerships are helping create solutions that are more locally relevant and sustainable.

- Empowering Indigenous Voices in Global Climate Discussions

The involvement of Explorers Club members in these collaborations has helped elevate the voices of Indigenous peoples in international climate discussions, such as those held by the Arctic Council and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Indigenous leaders from Alaska, Northern Canada, and Greenland are increasingly being invited to participate in global conversations about climate action, and their traditional knowledge is being recognized as a critical component in shaping climate policy.

The work done by Explorers Club members has also raised awareness about the disproportionate impacts of climate change on Indigenous communities, helping to secure greater support for climate justice initiatives and funding for adaptation efforts in these vulnerable regions.

- Conservation and Climate Mitigation

Collaborations between Explorers Club members and Indigenous peoples are contributing to effective climate mitigation efforts, such as preserving wildlife habitats, conserving carbon-rich ecosystems like tundra and peatlands, and reducing emissions from traditional land use practices. These initiatives help ensure that Arctic ecosystems are protected while also preserving Indigenous ways of life that rely on these environments.

~~~~~~~~

Some Final Thoughts on Climate Change:

Indigenous peoples of the Arctic are not only the most vulnerable to the effects of climate change, but they are also crucial allies in the global fight against it. Through collaboration with climate change experts, they bring unique perspectives, knowledge, and solutions that are vital to addressing the challenges posed by climate change in the Arctic. These partnerships enhance the accuracy of climate science, support the development of more effective adaptation strategies, and amplify the voices of Indigenous communities in climate policy debates.

The collaboration between Explorers Club members and Indigenous communities in Alaska, Northern Canada, and Greenland is proving to be a crucial aspect of combatting climate change in the Arctic. By combining modern scientific research with traditional ecological knowledge, these partnerships are providing innovative solutions to address the rapid changes occurring in these regions. The expertise of both scientists and Indigenous peoples is shaping more effective climate action strategies, promoting resilience, and ensuring that Indigenous voices are central to the global conversation on climate change. Through these collaborations, Indigenous communities are not only adapting to a changing world but are also driving forward the global effort to mitigate climate impacts and protect the planet’s most vulnerable ecosystems.

As the world continues to grapple with the climate crisis, the continued partnership between Arctic Indigenous peoples and climate experts will be essential in crafting just, sustainable, and effective solutions to protect both the environment and the cultures that depend on it.

Recommended Reading:

- Peter Freuchen: Book of the Eskimo

- Jonathan Waterman: Arctic Crossing and Into the Thaw

- Joe Sheppard: Canada’s Hidden People

- Reid Mitenbuler: Wanderlust

- Ken McGoogan: Dead Reckoning

About the Authors:

Bob Rein MN’24 is a member of The Explorers Club and an Ethnographer of North American Indigenous Cultures and as such, and in preparation for his travels to the far north, he began this research. His research was gleamed from the reading of books, watching videos, online research, and talking to fellow explorers that have the experience in the arctic. For a more in-depth insight into his explorations, please visit his website at https://www.reflectionsoffthegrid.com.

Allen Tuten was an experienced Ethnographer of Alaskan Indigenous cultures. From the late 1980’s to around 2014, he has studied, worked with, and lived with Inuit and other Indigenous peoples of Alaska having traveled there 26 times. In that immersion, he worked to improve the lives of the people, fostered trust, and learned much from the elders. His travels took him all over the state from Nome to Barrow (Utqiagvik), Southern Alaska, the Aleutian Islands, and the very remote island of Little Diomede, just a few miles from Russia. He worked with native people in both urban and rural communities. His observations of the issues the people have and still face are included in this paper.